The History and Ethical Dimensions of Precision Medicine in the Age of AI

In This Article

-

Precision medicine represents a profound shift from treating diseases to understanding the individuals who carry them.

-

As AI becomes central to medical decision‑making, ethical vigilance is essential to protect human dignity and autonomy.

-

The future of personalized healthcare depends on balancing innovation with compassion, transparency, and moral responsibility.

Precision medicine, or personalized medicine, is defined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as an approach that customizes prevention, diagnosis, and treatment to each individual by taking into account factors such as genetics, environment, lifestyle, and socioeconomic conditions. Unlike a one-size-fits-all approach, which relies on generalized treatment plans based on broad population averages, precision medicine seeks to optimize care by considering the unique biological and social determinants of health for each patient.

The U.S. government formally launched the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI) in 2015 to accelerate research and implementation of personalized healthcare solutions. One of the flagship programs under this initiative is the All of Us Research Program, which aims to collect genomic, clinical, and lifestyle data from over one million individuals from diverse backgrounds in the U.S. to build a comprehensive resource for medical research [1]. Further support for precision medicine came in 2016 with the passage of the 21st Century Cures Act, which allocated significant funding to biomedical research, including precision medicine, regenerative medicine, and drug development.

Similarly, Europe has also embraced precision medicine through organizations like the European Partnership for Personalized Medicine (EP PerMed) and the International Consortium for Personalized Medicine (ICPerMed). These initiatives facilitate international collaboration, regulatory frameworks, and research funding to advance the development and implementation of precision medicine across European healthcare systems.

A brief history of Precision Medicine

The idea of precision medicine dates to the time of Hippocrates, who is often regarded as the "father of medicine." He famously stated that “there is no disease, but the patient,” emphasizing that medical treatment should focus on the whole patient rather than just the disease. As medical science advanced, more concrete evidence supporting precision medicine emerged [2]. For instance, in the 19th century, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch demonstrated that individuals respond differently to infections, showing the diversity in disease susceptibility. Gregor Mendel’s experiments with pea plants in 1860s laid the foundation for genetics, revealing patterns of inherited traits from parents and their impact on getting certain diseases. In the 1950s, the field of pharmacogenetics emerged after discovering that drug response is linked to an individual’s genetic makeup, meaning that a medication’s effectiveness—or lack thereof—can depend on the genes inherited from one’s parents. In 1990, the Human Genome Project (HGP) started [3], [4] whose goal was to sequence the entire human genome, revolutionizing biomedical research and opening the door to genetically informed disease risk assessment and treatment strategies. After the completion of the HGP in 2003, the rise of Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) has enabled researchers to identify genetic variations associated with various diseases [5]. With the help of GWAS, many genes associated with diseases have been discovered and published in the GWAS catalog.

Examples of Precision Medicine

Several clinical examples of precision medicine already exist. One well-known case involves the CYP2D6 gene, which has multiple variants that affect how individuals metabolize medications. Depending on their CYP2D6 genotype, patients may process drugs quickly or slowly, influencing both effectiveness and side effects. Genotyping allows physicians to choose the right drug and dosage, improving outcomes and minimizing adverse reactions [6].

Another example is HER2-positive breast cancer, a subtype in which cancer cells overexpress the HER2 protein, leading to more aggressive tumors. Targeted drugs such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab block HER2 activity, slowing tumor growth and improving survival [7].

Similarly, in colorectal cancer, mutations in the KRAS gene determine whether patients respond to monoclonal antibody therapies like cetuximab or panitumumab. Only those with wild-type KRAS benefit from these treatments; patients with KRAS mutations require alternatives [8], [9]. Molecular profiling helps ensure that only patients likely to benefit receive these therapies, avoiding unnecessary treatments, reducing costs, and lowering the risk of side effects. This approach has inspired the development of molecular subtyping across many cancer types [10–13].

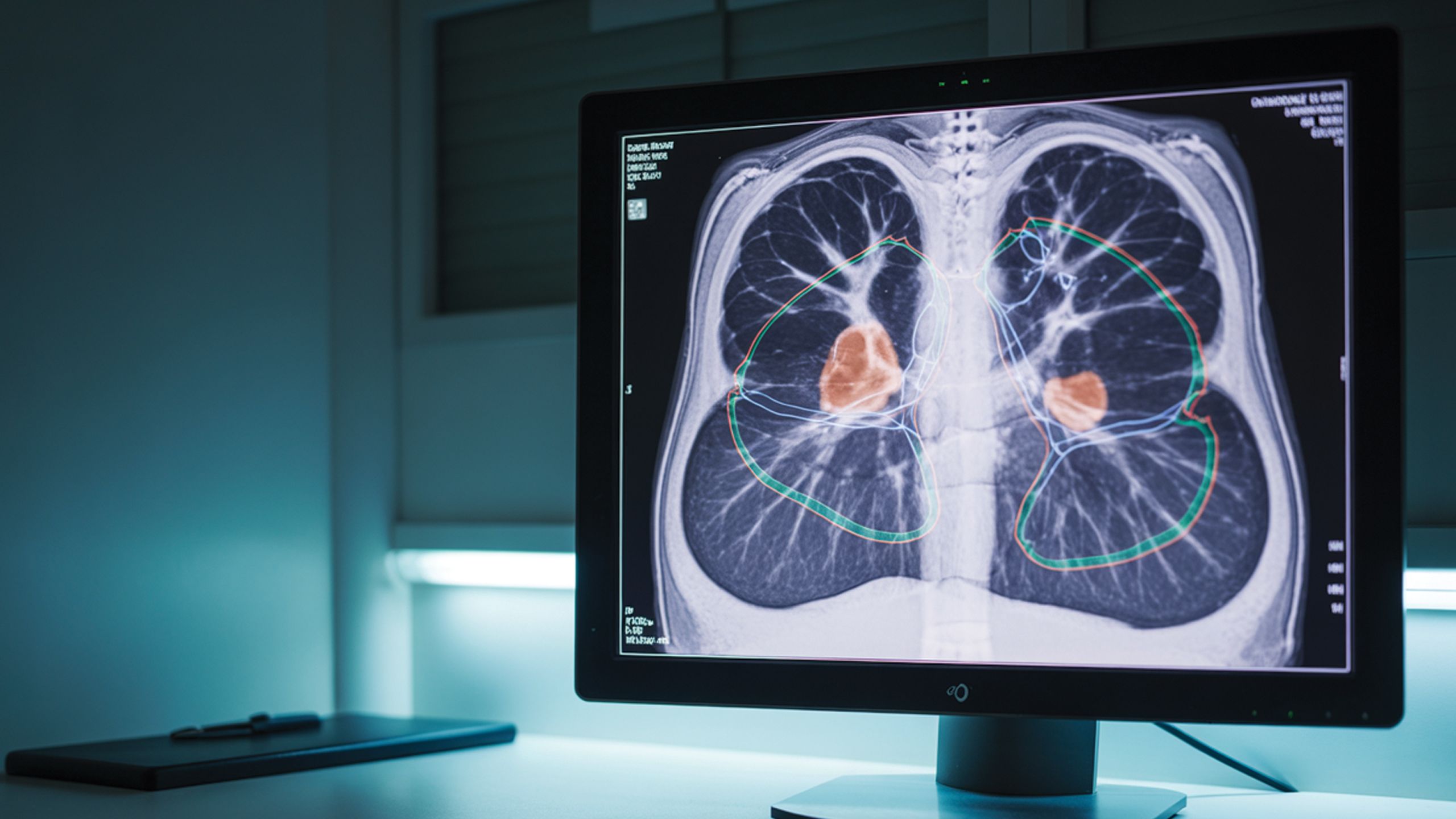

An emerging area, precision radiomics, uses artificial intelligence and advanced imaging to extract detailed tumor characteristics from medical scans. When integrated with genomic and clinical data, radiomics enables highly tailored radiotherapy plans that deliver optimal radiation doses while protecting healthy tissue, ultimately improving patient outcomes [14].

Computational methods and AI

Despite the promise of precision medicine, making personalized treatments widely accessible remains challenging. Although the goal is to tailor care using genetic, clinical, and lifestyle data, scaling such solutions has proven complex. Several companies have attempted it, but some high-profile efforts have struggled. One well-known example is IBM’s Watson for Oncology, which aimed to use AI for cancer diagnosis and treatment recommendations but ultimately fell short due to biased training data, limited clinical context, and difficulty incorporating real-world expertise.

Recent advances in generative AI and large language models, however, have renewed optimism. Unlike earlier rule-based systems, modern AI can analyze vast patient datasets, detect subtle patterns, and generate insights that may not be immediately apparent to clinicians. This opens new possibilities for improving diagnosis, treatment selection, and patient outcomes.

AI contributes to precision medicine in several ways. It can identify meaningful patterns in clinical records, lifestyle factors, and environmental exposures that correlate with treatment response. By analyzing multimodal data—including genomics, electronic health records, imaging, and wearable devices—AI can determine which patient features matter most and how they interact, guiding more individualized care.

Another key contribution is predicting how a specific patient will respond to a drug or therapy. Deep learning models trained on large datasets can estimate treatment effectiveness, helping clinicians select the most beneficial option. This is essential: missing a life-saving therapy can be fatal, while receiving an ineffective treatment imposes financial, emotional, and physical burdens. AI-driven prediction models help maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing risk and side effects.

Ethical aspects

While precision medicine offers great potential, it also raises important ethical concerns. A major issue is ensuring that AI models used in healthcare are fair and unbiased. Many systems are trained on datasets that fail to represent diverse populations, leading to unequal or misleading outcomes. Addressing this requires more inclusive data collection and representative training sets. Initiatives like the All of Us Research Program are crucial for reducing bias and ensuring that precision medicine benefits all patients rather than reinforcing existing disparities.

Genetic data privacy is another central concern. Strict safeguards are needed to control who can access such sensitive information and for what purposes. If genetic data were exposed, individuals and their families could face discrimination, stigma, or privacy violations—for example, employers or insurers misusing information about disease risk. Because genetic data is hereditary, breaches affect not only one person but also their relatives and future generations. In the U.S., the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008 prohibits discrimination based on genetic information in employment and health insurance, but ongoing policy updates will be essential as technology evolves.

Gene editing, especially germline modification, remains one of the most controversial ethical issues in precision medicine. Somatic editing affects only the treated individual, but germline editing alters DNA in eggs, sperm, or embryos in ways that can be inherited. Although this could prevent certain hereditary diseases, it raises profound moral and societal questions. Misuse could permanently alter the human gene pool or worsen inequalities, and future generations—who cannot consent—would be directly affected. For these reasons, germline editing continues to be one of the most debated topics in bioethics and precision medicine [16].

Future challenges

There are several major challenges to making precision medicine widely accessible.

- Democratization

Precision medicine must work for people across different demographic and socioeconomic groups. This requires both inclusive datasets and access to the necessary tools worldwide. Mobile health apps that measure basic biological variables could support early diagnosis and preventive care, but scaling treatments globally—and generating high-quality data such as whole-genome sequences—still faces financial and regulatory barriers.

- Scalability

Precision medicine depends on analyzing massive datasets to discover biomarkers and guide treatment decisions. This requires substantial computational resources and continuous model updates as new data appears. Secure data-sharing across hospitals and countries is essential. Federated learning offers a possible solution by allowing collaborative model development without moving raw patient data [17]. Global coordination—potentially led by organizations like the WHO—is needed to build models that reflect ethnic, racial, and geographic diversity.

- Handling missing and noisy data

Large biomedical datasets often contain confounding, incomplete, or context-dependent information. Without proper interpretation, this can produce misleading insights. For example, someone visiting the emergency room after an acute trauma may have elevated vitals that do not represent their usual health, which could distort predictive models. External events—such as wildfires triggering asthma spikes—can also skew data if not contextualized. Precision medicine must distinguish meaningful patterns from noise while preserving relevant context.

- Small sample sizes

Rare diseases often have very few patients, making traditional clinical trials impractical. Transfer learning offers one solution: models trained on large populations can be fine-tuned for small, specific cases. Digital twins—virtual replicas built from a person’s genetic, physiological, and clinical data—can simulate treatment responses and are already being explored in cardiology [18]. Adaptive trial designs, such as N-of-1 studies, also help evaluate treatments for individual patients, while international data-sharing efforts can expand sample sizes for rare disease research [19].

- Broadening precision medicine across diseases

Although much progress has been made in oncology, precision medicine must be expanded to cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, metabolic, and infectious diseases. Advances in genomics and multi-omics have revealed biologically distinct subtypes within many conditions. For instance, type 2 diabetes, once treated as a uniform disorder, now includes at least five genetically and metabolically distinct subgroups [20], allowing for more targeted therapies based on insulin sensitivity, beta-cell function, and other individual factors.

Conclusion

In the era of big data and AI, the field of precision medicine has great potential to improve across a wide range of diseases. In the future, precision medicine would help preventive medicine efforts for early diagnosis and intervention of diseases by providing tailored treatment and intervention plans. There are several challenges, both technological, social, and ethical, that need to be overcome. Ethicists, policy makers, scientists and medical professionals need to work collaboratively to provide solutions to these challenges to make precision medicine a routine component of healthcare.

References

- All of Us Research Program Investigators et al., “The ‘All of Us’ Research Program,” N Engl J Med, vol. 381, no. 7, pp. 668–676, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937. Also see Yalcin, “Precision Medicine for Everyone: All of Us Research Program Initiative,” The Fountain 166, July 1, 2025.

- S. Visvikis-Siest, D. Theodoridou, M.-S. Kontoe, S. Kumar, and M. Marschler, “Milestones in Personalized Medicine: From the Ancient Time to Nowadays—the Provocation of COVID-19,” Front. Genet., vol. 11, Nov. 2020, doi: 10.3389/ fgene.2020.569175.

- E. S. Lander et al., “Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome,” Nature, vol. 409, no. 6822, pp. 860–921, 2001.

- J. C. Venter et al., “The sequence of the human genome,” science, vol. 291, no. 5507, pp. 1304–1351, 2001.

- W. S. Bush and J. H. Moore, “Chapter 11: Genome-Wide Association Studies,” PLOS Computational Biology, vol. 8, no. 12, p. e1002822, Dec. 2012, doi: 10.1371/ journal.pcbi.1002822.

- N. A. Nahid and J. A. and Johnson, “CYP2D6 pharmacogenetics and phenoconversion in personalized medicine,” Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 769–785, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1080/ 17425255.2022.2160317.

- S. M. Swain et al., “Pertuzumab, Trastuzumab, and Docetaxel in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 372, no. 8, pp. 724–734, Feb. 2015, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413513.

- A. Bardelli and S. Siena, “Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to Cetuximab and Panitumumab in Colorectal Cancer,” JCO, vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1254–1261, Mar. 2010, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6116.

- C. Tan and X. Du, “KRAS mutation testing in metastatic colorectal cancer,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 18, no. 37, pp. 5171–5180, Oct. 2012, doi: 10.3748/ wjg.v18.i37.5171.

- R. Mclendon et al., “Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways,” Nature, vol. 455, no. 7216, pp. 1061–1068, 2008, doi: 10.1038/nature07385.

- D. C. Koboldt et al., “Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours,” Nature, vol. 490, no. 7418, pp. 61–70, Oct. 2012, doi: 10.1038/ nature11412.

- C. J. Creighton et al., “Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma,” Nature, vol. 499, no. 7456, pp. 43–49, Jul. 2013, doi: 10.1038/ nature12222.

- “Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma,” Nature, vol. 511, no. 7511, pp. 543–550, Jul. 2014, doi: 10.1038/nature13385.

- H. J. W. L. Aerts, “The Potential of Radiomic-Based Phenotyping in Precision Medicine: A Review,” JAMA Oncology, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 1636–1642, Dec. 2016, doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2631.

- L. Bonomi, Y. Huang, and L. Ohno-Machado, “Privacy challenges and research opportunities for genomic data sharing,” Nat Genet, vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 646–654, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0651-0.

- G. Rubeis and F. Steger, “Risks and benefits of human germline genome editing: An ethical analysis,” ABR, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 133–141, Jul. 2018, doi: 10.1007/s41649-018-0056-x.

- M. Aledhari, R. Razzak, R. M. Parizi, and F. Saeed, “Federated Learning: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 140699–140725, 2020.

- J. Corral-Acero et al., “The ‘Digital Twin’ to enable the vision of precision cardiology,” European Heart Journal, vol. 41, no. 48, pp. 4556–4564, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa159.

- E. O. Lillie, Patay ,Bradley, Diamant, Joel, Issell ,Brian, Topol ,Eric J, and N. J. and Schork, “The N-Of-1 Clinical Trial: The Ultimate Strategy For Individualizing Medicine?,” Personalized Medicine, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 161–173, Mar. 2011, doi: 10.2217/pme.11.7.

- M. Pigeyre et al., “Validation of the classification for type 2 diabetes into five subgroups: a report from the ORIGIN trial,” Diabetologia, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 206–215, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s00125-021-05567-4.